Hopper wagons at the base of the truck hoist which had a capacity of over 3,000 tonnes in eight hours. One wagon sits on the gantry. Note the single vertical cylinder. G&C Hoskins Ltd, The Blue Book 1915

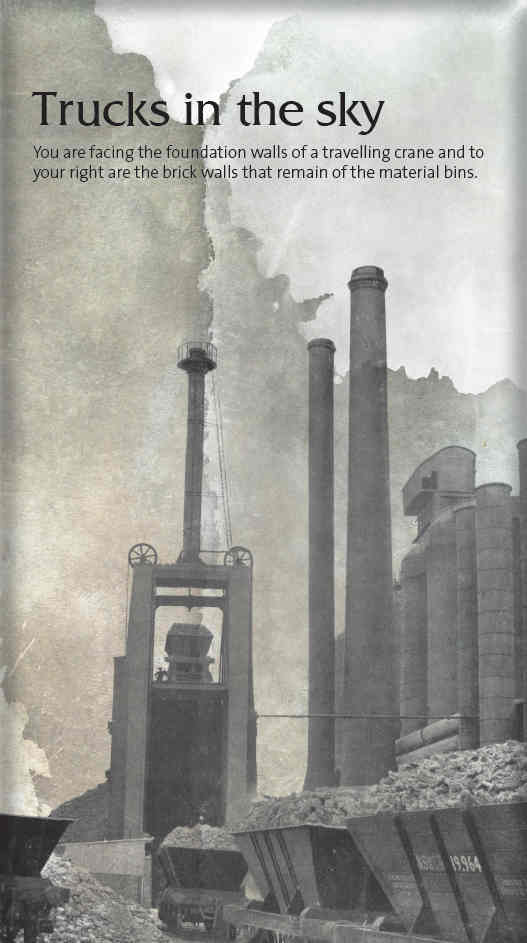

Hoisting the trucks

The raw materials for iron making—iron ore, coking coal and limestone—arrived at the site by rail in hopper trucks which were run onto the weighbridge. The ‘weigh boy’ then left the cabin, crossed the rail line and signalled a labourer who pushed the loaded wagon onto the platform of the steam lift and applied the brakes. The entire truck was hoisted up 10 metres to the gantry rail and the contents were discharged at the appropriate bin. The empty truck was manually pushed along the gantry to the ‘truck drop’. A system of counterweights helped lower the truck back onto the railway. The only fabric that remains of the gantry is the footings.

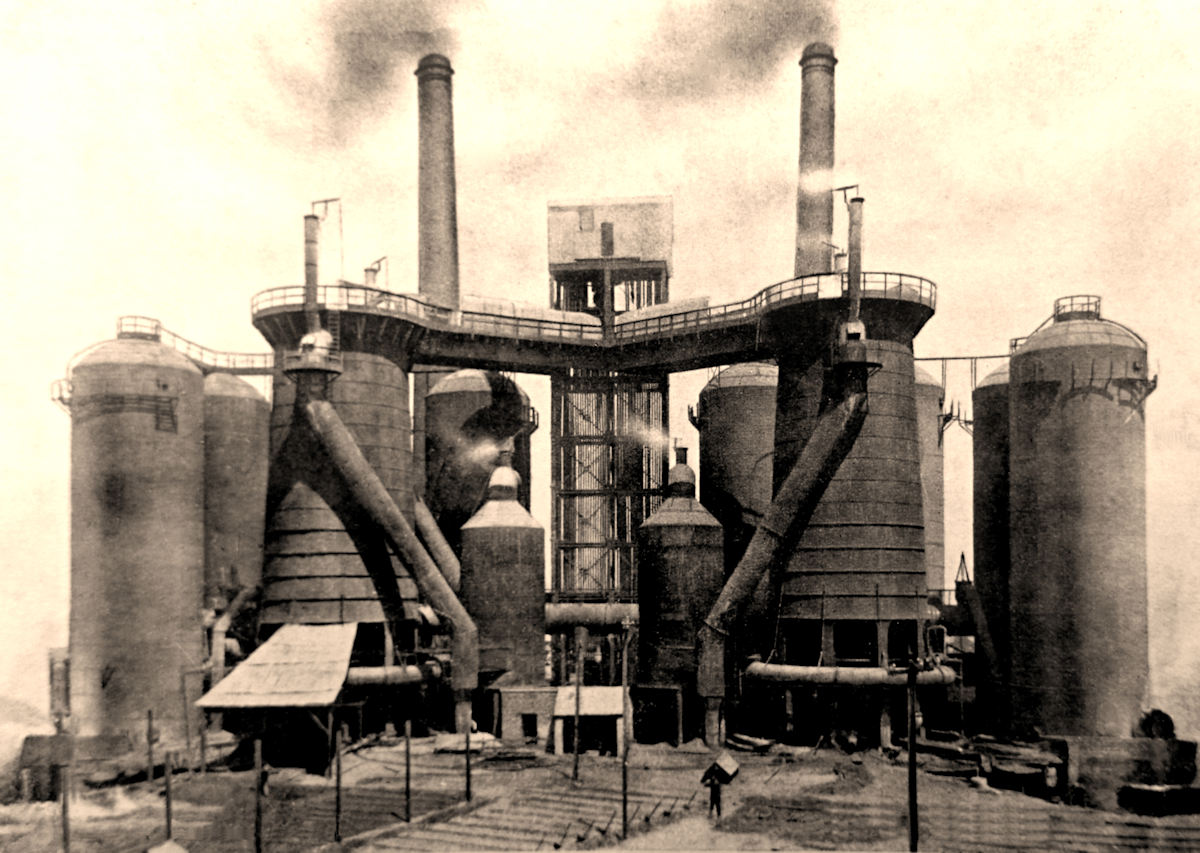

Daddy long legs

Two elevated parallel concrete walls behind the materials store once formed the base of a travelling crane that was used to stockpile

materials, especially iron ore. The crane – an electrically driven portal crane – was nicknamed “daddy long legs.”

Material bins

To the north of the brick walls were six highwalled timber bins that held limestone and iron ore. They were demolished in 1928-29. The two coke bins were originally defined by three brick walls, two of which remain. The metal bars and bolts on the south wall are all that is left of horizontal dividers. Abrasions high on the walls are probably from coke discharged from the trucks on the gantry above. The coke bins were made of brick for fire protection and to support the gantry. The back of the bins were timber planks. Iron plates and bolts on the floor of the coke bins are vestiges of the coke screen. As coke left the bin it was screened to remove fines and improve the operation of the furnace. The barrows used to carry the coke to the furnace were known as ‘banana carts’.

The McMyler 5-tonne electric portal crane transfers excess limestone from below the gantry to the stockpile. The shed at the base of the wagon hoist (right) contained its control mechanism. The portal crane later worked in Port Kembla. Department of Mineral Resources courtesy of Bob McKillop.

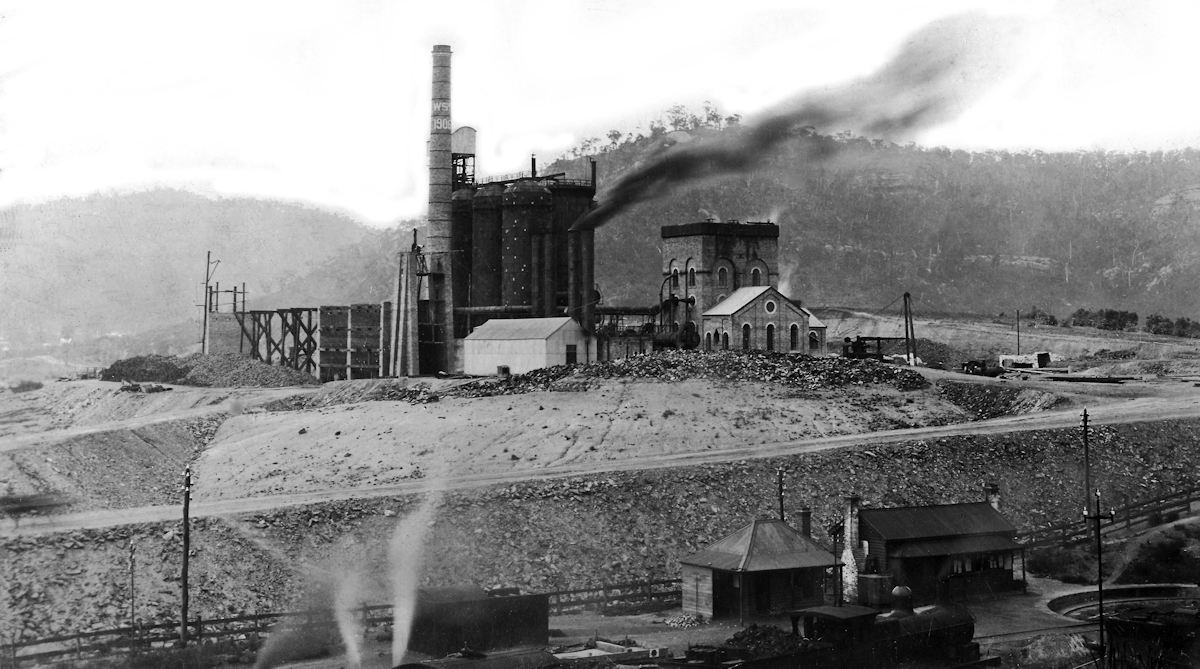

Taken from Inch St c1910: Large piles of slag partially obscure the Davy engine house, boiler house and chimneys to the right. The photograph shows the full extent of the steam lift, gantry and truck drop that serviced the material bins. Jim Longworth Collection courtesy of the Lithgow Library Learning Centre

Stoves and chimneys

Here you can see the base to the blast furnace platform. The semi-circular projections (left and right) are the brick bases for the chimneys which serviced the stoves. The arches and tunnels that pierce the brick revetment wall allowed workers to access and clean the flues.

William Sandford’s No. 1 furnace, to the right, was completed in 1907 and originally had three Cowper stoves, each 22.5 metres high and almost 7 metres.

in diameter. They were the first regenerative stoves used for blast heating in Australia. The bottom plate for stove No. 2 lies on its side against the wall. The bottom plate for stove No. 1 is in place on the platform.

‘On gas’ or ‘on blast’

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace which considerably reduced the fuel consumed. Hot blast was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution.

The stoves were alternately heated by the burning of blast furnace gas and then used to heat the blast. This is known as regenerative heating. As one stove was heating up – ‘on gas’ – another stove was heating cold air – ‘on blast’. The air was initially provided by the Davy engine and thereafter generations of turbine engines. Three Cowper stoves were needed to provide a continuous supply of hot air to the furnace.

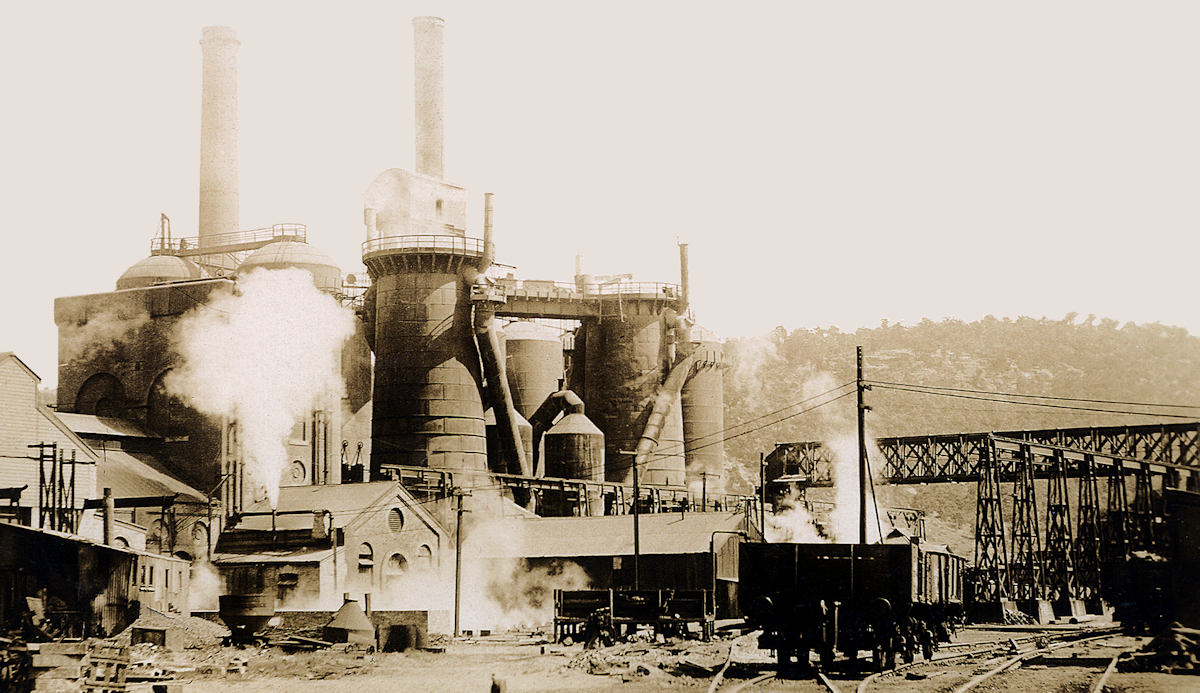

Tower Hoist

The tower or furnace hoist was an open frame, steel structure with a shelter shed at the top. Second only in height to the chimneys, it provided a means of lifting raw material for top loading the blast furnaces. Barrows were wheeled across a catwalk to the ‘charging bell’ at the top of each furnace. A steam engine mounted on the ground powered the hoist.

There are no physical remains of the hoist which was positioned in the large recess in the retaining wall between the stoves.

“Between the two furnaces was a steel cage that conveyed materials to make pig iron to the top of the furnaces. Huge men, stripped to the waist and covered in grime wheeled two wheelbarrows filled with the requisite materials onto this lift.

Wedged in between the barrows a man blew a whistle. We were off. To call this contraption a lift conjures up images of lifts in city shops. Alas this was not the same thing at all. It jerked and weaved and made it to the top in a series of kangaroo-like leaps, all the while a frightful din went on and the acrid smell of smoke and escaping fumes of the furnace grew worse as it went higher.

Finally the monster would grind to a halt, more hefty men wheeled out the barrows and tipped the contents into the furnaces.” Recollections of Mavis Britten Mortlock and Betty Mortlock.

Lithgow Library Learning Centre, LDHSA papers.

The blast furnace in operation during 1907. The pig-beds are in the foreground and the Davy engine house and pump house are to the left. To the far right the wagon drop from the gantry is clearly visible. The dominant feature on the site is the barrow lift.

The Department of Mineral Resources courtesy Bob McKillop

Old Technology

William Sandford chose designs for the first blast furnace in 1905, adopting British technology of the time. Twenty years behind innovations in the USA, the obsolete technology led to a reliance on the manual labour of 100 men to complete heavy and difficult tasks.

Traditional blast furnaces were loaded with raw materials from the top. The iron ore, coke and limestone were loaded into large two-wheel barrows and hauled to the ‘tower hoist’ which then jumped and jerked its way to the top of the blast furnace. Each barrow might contain up to 500 kg of coke or limestone but if the barrow contained iron ore it could weigh over 700 kg. The barrowmen stumbled and twisted under the strain.

Backbreaking and treacherous

After the treacherous trip to the top of the furnace the barrowmen manually tipped the material onto the ‘charging bell’ which sealed the furnace. The ‘top man’ decided when the charge was correct and, shielded behind a steel shelter, he would lower the bell. The material then dropped into the blast furnace.

Eighteen tonnes of material were carted in 25-27 round trips per shift for 8 shillings. Working the furnace was backbreaking and treacherous with extreme changes in temperature and exposure to toxic gases and waste only adding to the harsh experience.

“A hand brake controlled the descent of the wagon drop when the wagon had been placed on it. Two men operated the long handle, pinning it down while the wagon gravitated onto the drop tray. A slight release of the brake controlled the lowering of the wagon. The brake was applied again as the wagon rolled off the drop tray onto the receiving siding. A controlled release of the brake allowed the empty tray to rise again to the top of the gantry. ‘

Bob McKillop, Furnace, Fire and Forge, 2006

This photograph taken after 1913 shows the truck drop to the left. The gantry is fully loaded with rail trucks. To the right the boiler house is being further developed and the second Parsons engine house has been built. Charles Hoskins journal

Great skill required

Wagons were hoisted onto the 10 metre high gantry by a steam hoist. This required great skill on the part of the operator. When at the correct height, the wagons ran down a slight grade to be positioned at the appropriate bin. After discharging its contents into the bin the wagon proceeded to the ‘wagon drop’ .

Working the gantry was dangerous with minimal lighting available and so it only operated in daylight hours.

The brick wall was both a bin wall for ore and the support for the end of the gantry line. The wall is scarred with the marks of the giant counterweight that slowed the descent of the truck platform and assisted in raising it after trucks had been rolled off.

Keepers House

A substantial brick building provided shelter to ‘the keeper’, who looked after the furnace, in case of the furnace ‘blowing out’.

Dust extractors

Dust catchers were large cylindrical steel apparatuses located adjacent to each furnace and connected to the furnace by a vent. They extracted dust from the atmosphere during the iron smelting process.

Pug mills

Although not appreciated from this location, the remains of a ‘pug mill’ lay to the north of blast furnace No 2. The mill was used to grind clay materials during construction in 1906. It was removed to Port Kembla in 1928.