“You are a new chum here, Mr Hoskins,

and do not understand the working

men of the valley.”

Robert Pillans, leader of the Ironworkers Union and Mayor of Lithgow

No smoking

G&C Hoskins Ltd took over the Lithgow Iron and Steel Works in 1908 and immediately set out to change work practices which provided a focus for unrest among the workers.

Charles Hoskins failed to appreciate how entrenched union-run labour practices were in Lithgow. By 1911 there were clear tensions

between management and the strongly unionised workforce.

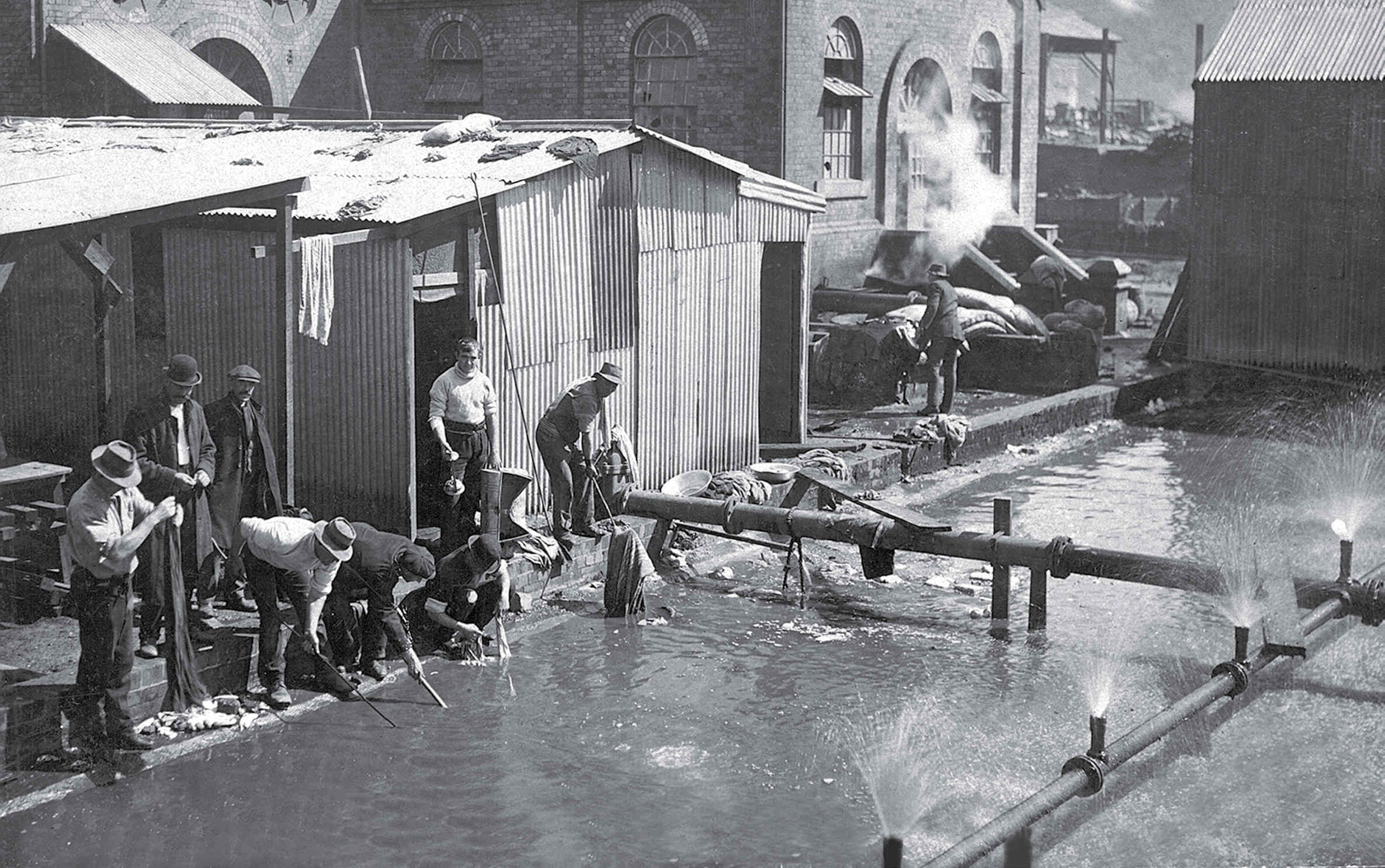

Staff of G&C Hoskins Ltd, 1909. BHP Biliton archives courtesy of Bob McKillop

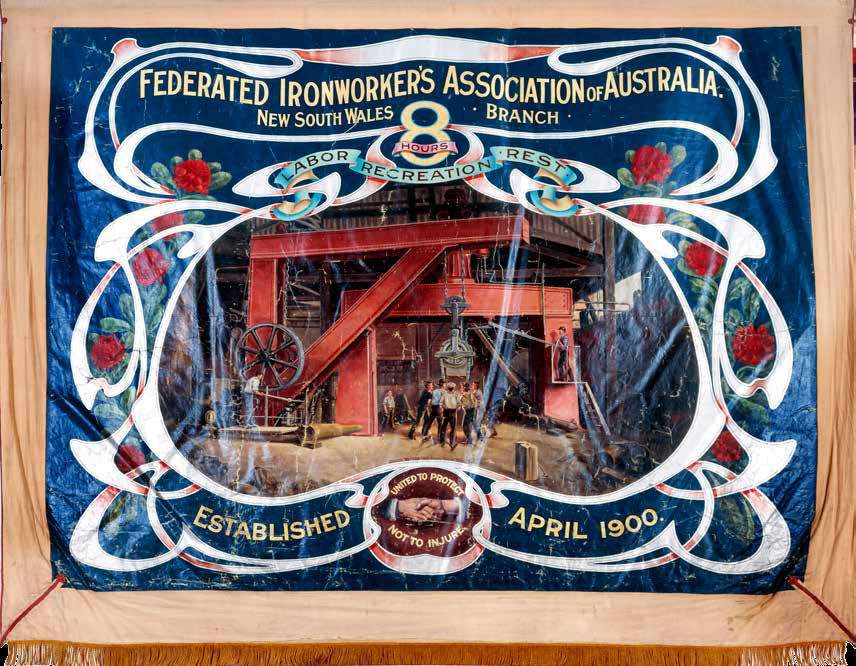

The 1914 Eight-hour Day parade. The small banner reads, ‘Forging Ahead – The Workers Industrial Union – is The One, Big Union’.

Lithgow Library Learning Centre

Strike blamed on ‘agitators’

In February 1911 Carcoar miners and Ben Bullen quarrymen went on strike. Hoskins blamed “agitators” and wrote to the Lithgow Mercury,

“ working people should treat a strike as they would a venomous snake – that is take every means in their power to kill it.”

Lithgow Mercury, 10 February 1911

Refusing to negotiate, Hoskins prosecuted strikers under the NSW Industrial Disputes Act. With few exceptions the strikers were fined. The strike was finally settled informally at the Lithgow Show dinner after Hoskins met with senior Labor government politicians.

G&C Hoskins Ltd took over the Lithgow Iron and Steel Works in 1908 and immediately set out to change work practices which provided a focus for unrest among the workers.

Charles Hoskins failed to appreciate how entrenched union-run labour practices were in Lithgow. By 1911 there were clear tensions

between management and the strongly unionised workforce.

500 Workers stood down

“…in these very ordinary proceedings there lays the germ of serious trouble.”

Lithgow Mercury, July 1911

James Cairns was suspended by Hoskins for missing work to attend a union meeting in Sydney and Tunnel Colliery workers reacted by calling a general strike. Hoskins responded by withdrawing a wage rise he had given the miners on the understanding that they would not strike. When Western Coalfields workers ‘went out’ in support of the strikers, Hoskins stood down 500 workers and non-union (‘blackleg’ or ‘scab’) labour was bought in to keep the blast furnace operating.

Lithgow women back their men

On 23 August the blast furnace workers joined in the strike action. The Lithgow community rallied behind the workers and women were

publicly active in their support. The strike dragged for nine months and, before it ended, armed police would confront angry, missile-hurling strikers where you are standing.

“Lithgow resembles nothing so much as a brimming cauldron, bubbling and simmering, and threatening each minute to boil over.”

Sydney Morning Herald 1 September 1911

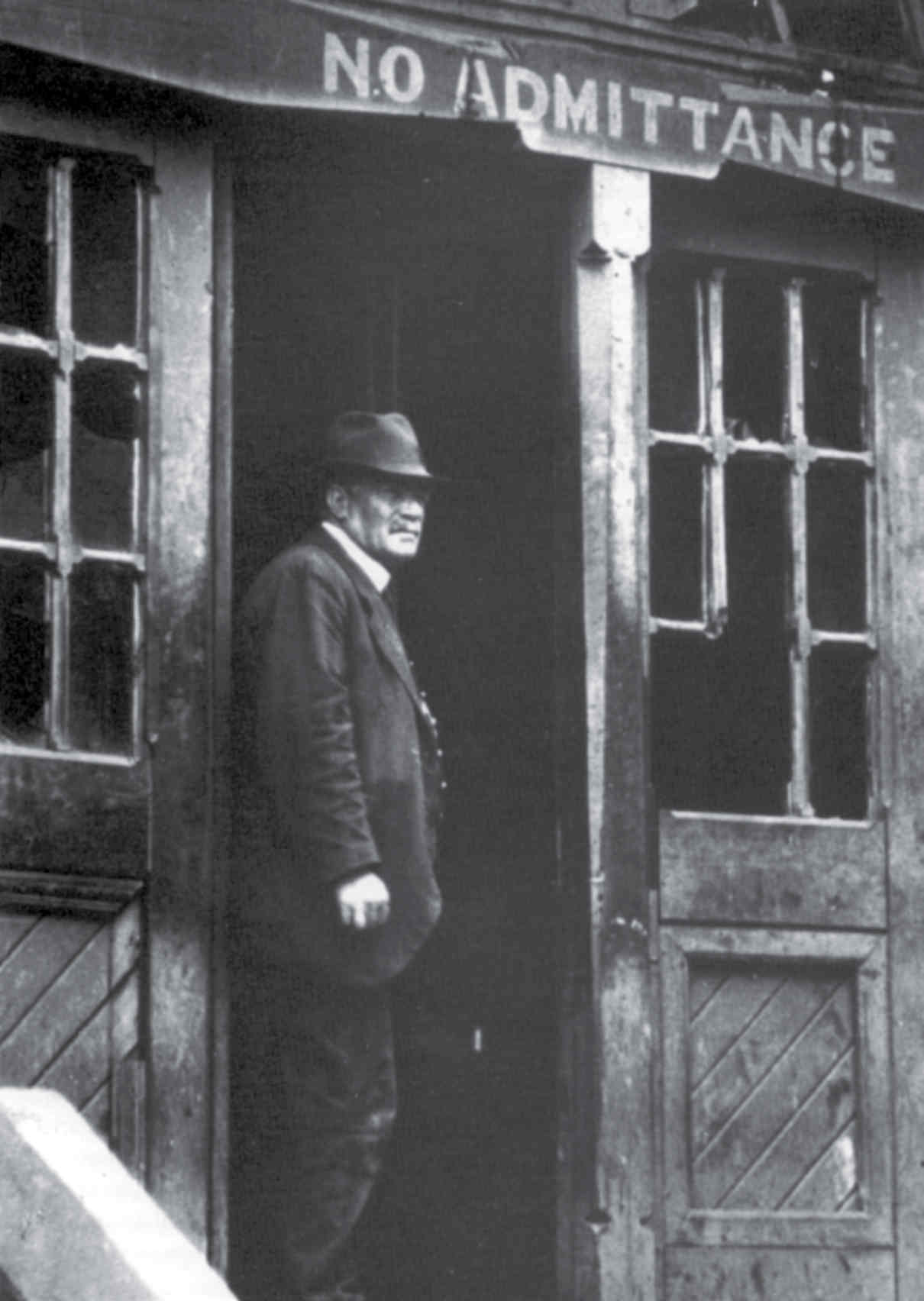

Charles Hoskins looks out from the engine house where he and his sons had sheltered on the night of the riot. Lithgow District Historical Society Collection

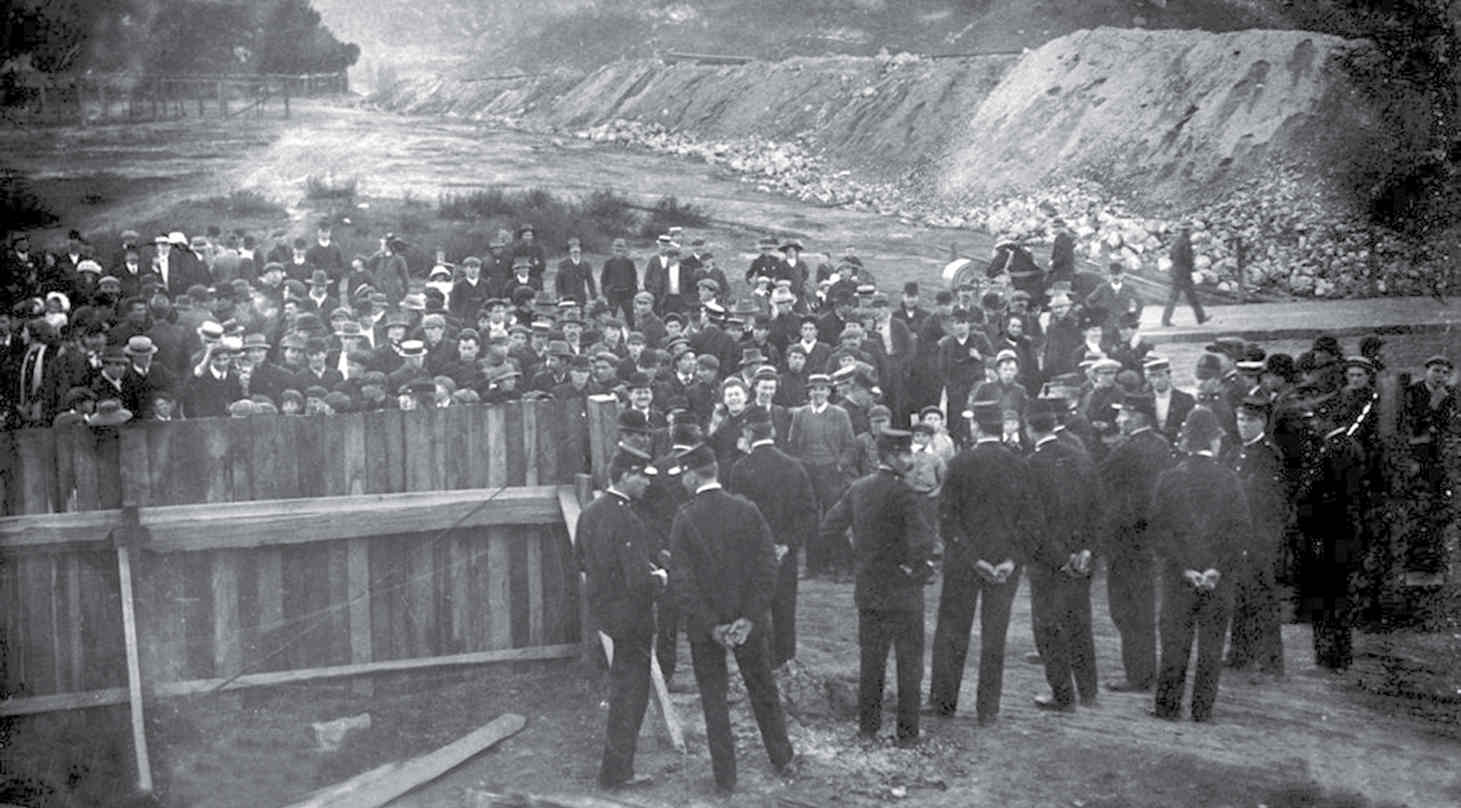

Police guarding the entrance to the blast furnace

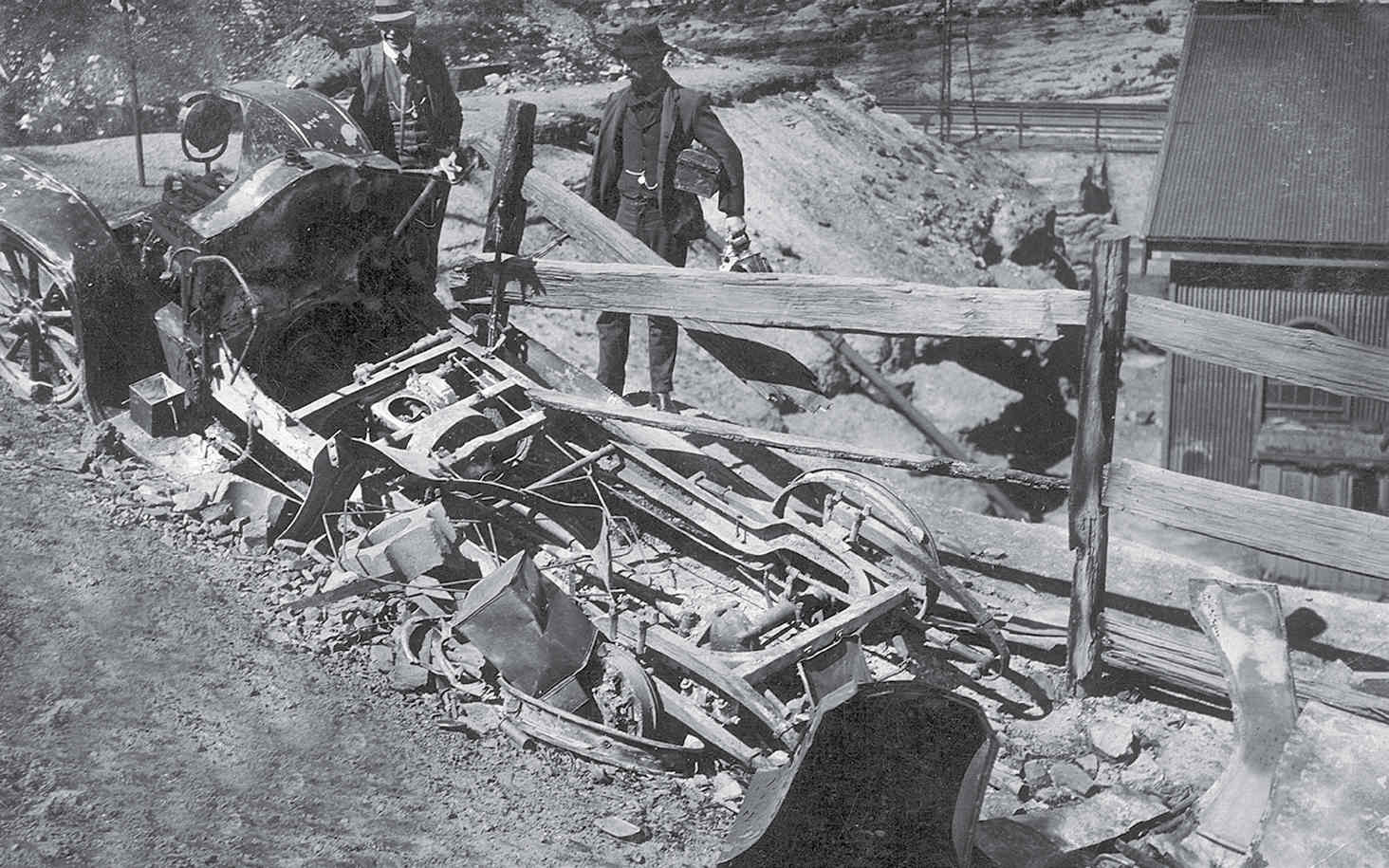

Charles Hoskins surveys the burnt out wreck of his Renault. Lithgow Library Learning Centre

Strikers and supporters

On 29 August 1911, over 2000 strikers and supporters gathered in protest at the picket line outside the blast furnace. As they waited for the 6 pm change of shift, the foreboding tune of the “Dead March” floated across the crowd. When a group of unruly youths started to stone the strike breakers the frenzied mob surged forward. Fearing for their lives, Hoskins’ three sons barricaded themselves inside the Davy engine house with the non-unionists. Charles Hoskins, armed with a revolver, arrived through the back door.

Widespread destruction

Hoskins refused to address the crowd inciting a rampage. Hoskins’ prized Renault 16/20 was rolled down an embankment and torched. The quarters of the “scab” labourers were ransacked. By the next morning the local police had control of the situation. The Lithgow Mercury recorded, “ A feeling of keen regret will be felt by almost every resident of Lithgow over the outbreak of violence…

Those who rushed the blast furnace appear to have acted in sudden blind impulse.”

Guerrilla tactics

Confronted with the power of the state, strikers turned to guerrilla tactics. Attempts were made to sabotage company trains and a house was bombed. The picket lines were maintained and non-union workers were constantly under threat of violence.

Strikers prosecuted

Several arrests and convictions followed and G&C Hoskins prosecuted Ironworks Tunnel miners under the Master and Servants Act for being absent from their work without permission. The strike was eventually settled on 17 April 1912. Nine months of strike action had serious financial consequences for the company, and led to a cut in wages.