Lithgow Valley Iron Company

Lithgow Valley Iron Company was founded by colourful Canadian James Rutherford of Cobb & Co., John Sutherland, Minister for Public Works, and Daniel Williams, an Englishborn builder who had managed the construction of the Main Western Railway west of Rydal.

Commercial iron

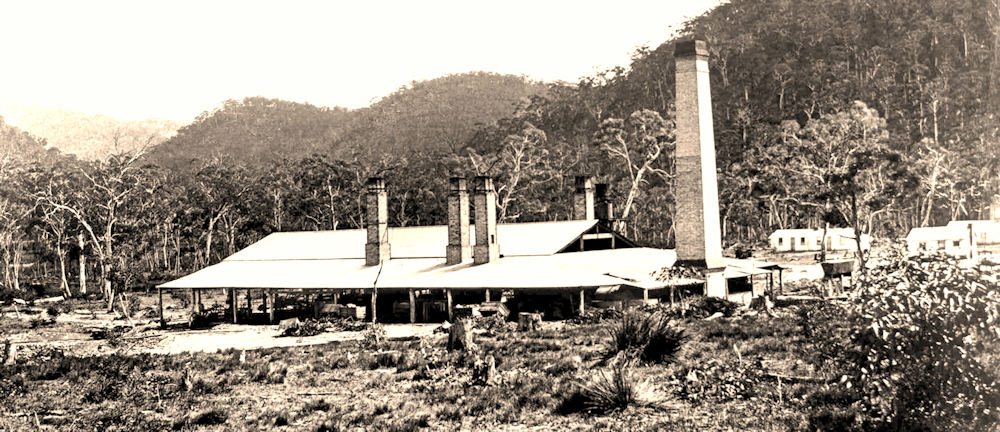

The company employed Enoch Hughes to build a blast furnace and, in 1875, iron ore was first smelted in the Lithgow valley. The Esk Bank Ironworks was one kilometre west of this site (now Marjorie Jackson Sporting Complex). Daniel Williams led the operation for five years, finally retiring due to poor health. He is widely regarded as laying the foundation of the Australian iron industry.

Failed enterprise

Lacking strong leadership, facing high freight charges and using ore of variable quality, the venture was enable to compete with imported pig iron. The blast furnace ceased operation in 1882 and the Lithgow Valley Iron Company was defunct by 1884. The iron works continued under the Ironworkers Co-operative Association as a foundry, re-rolling pig iron and using scrap metal.

Expansion

William Sandford purchased Esk Bank Iron Works and the Esk Bank Estate from James Rutherford in 1890. He imported a Siemens-Martin open hearth furnace and made the first commercial steel in Australia on 24 April 1900. In the early 20th century, steel was replacing iron and was seen as the metal of the future.

In 1905 Sandford won a contract to supply the NSW Government with iron and steel. He borrowed heavily and expanded the iron and steel works at a time when scrap iron was becoming more difficult to procure at a competitive price.

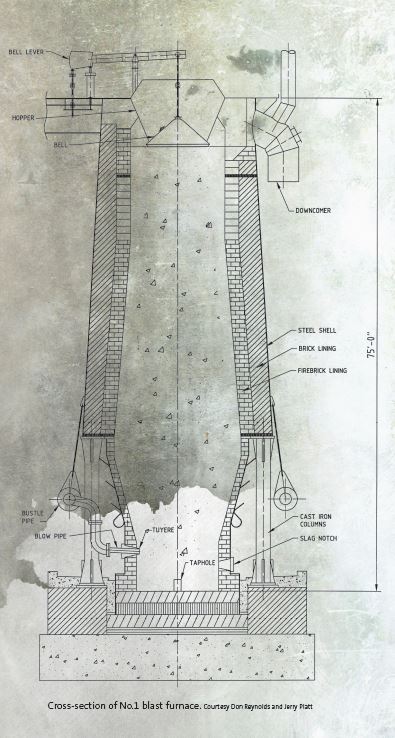

In 1906 William Sandford began construction of a blast furnace on this site to ensure an adequate supply of pig iron for his iron and steel works.

A modern blast furnace

Here, on 13 May 1907, Australia’s first modern blast furnace was ‘blown in’. Sandford’s blast furnace was based on typical English designs of the late 19th century. It was massive compared to its Australian forerunners. Linked by rail to the iron and steel works, one kilometre away,the blast furnace had the potential to produce 1000 tonnes of pig iron per week.

William Sandford was heavily in debt and without promised government assistance, he was forced to sell

G&C Hoskins take over

G&C Hoskins Ltd took control of the business in 1908.

As Australian industry expanded, there was high demand for iron and

steel. The Hoskins brothers met this demand, building a second blast furnace in 1913.

While the works flourished during WWI, the increasing cost of raw materials and freight eroded the

profitability of the plant. G&C Hoskins Ltd formed Australian Iron and Steel in 1928 and transferred its

blast furnace operations to Port Kembla soon after.

“The politics of protection were to become a dominant theme in the history of the Australian iron and steel industry.”

Bob McKillop: Furnace, Fire and Forge

Social change

Lithgow’s industrial development and strong tradition of organised labour became a symbol of the Australian economy.

The development of the capacity to produce commercial quantities of steel meant the former colonies had progressed to a self

reliant nation.

Labour disputes in Lithgow, in the early twentieth century, helped shape the future of industrial arbitration in NSW.

Politics of protection

Australian iron producers struggled to be competitive when pig iron was imported cheaply as ship’s ballast.

Local iron and steel producers lobbied the Federal government for protection from cheaper imported products.

Various tariffs helped the fledgling industry to survive through the early 20th century.

Coal, steel and rail

The Lithgow blast furnace ruins are the most significant symbol of the industrial identity of Lithgow. The three elements of coal, steel and rail forged Lithgow’s proud heritage as the “cradle of the iron and steel industry in Australia.”

Guests arriving for the opening of William Sandford’s blast furnace on 13 May 1907. The steelworks brass band (left) greets them and the banner proclaims “Success To Local Industry”. BHP Billiton Archives, courtesy Bob Mc Killop

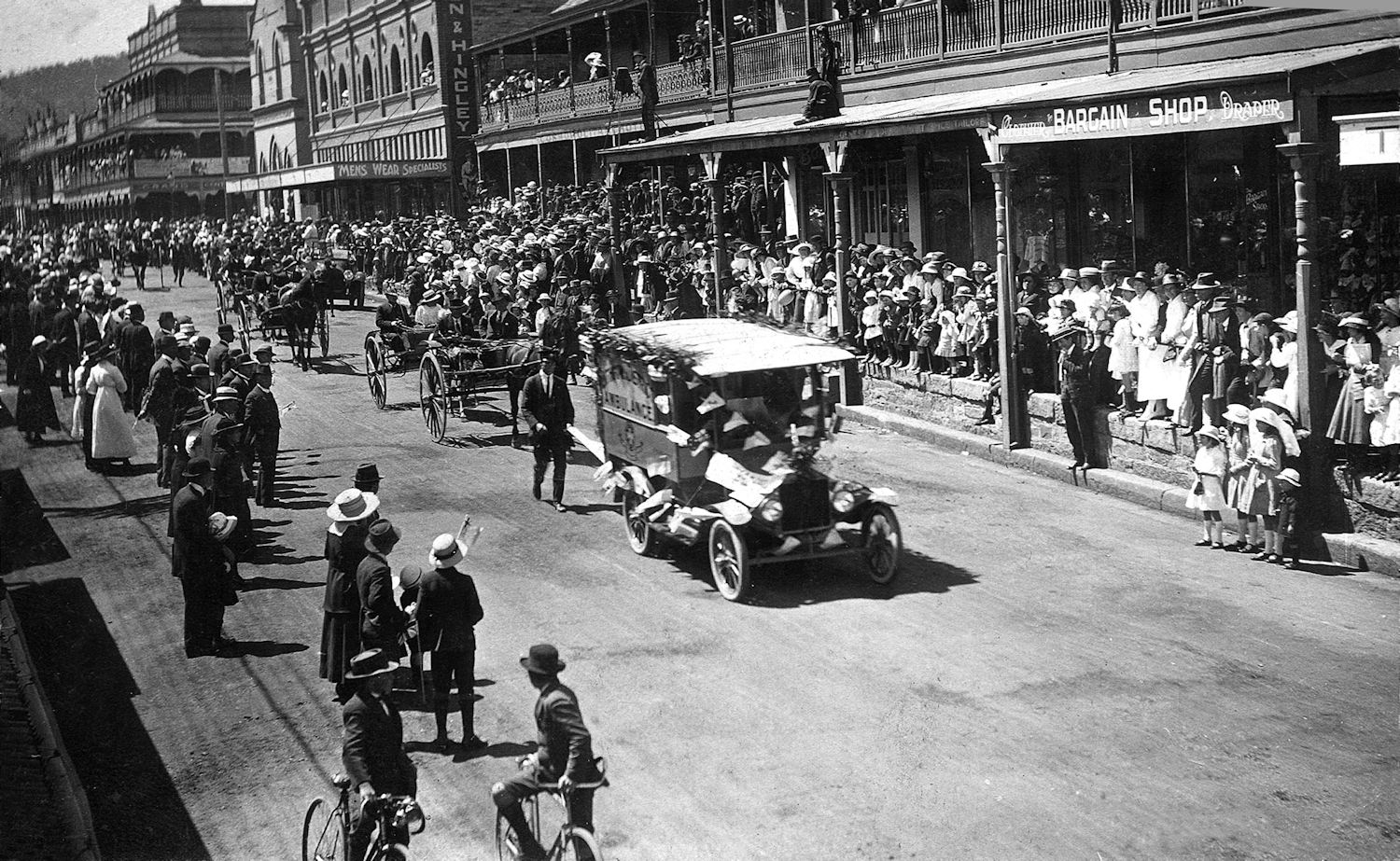

The 1914 Eight-hour Day procession in Main Street. Lithgow Library Learning Centre, DHS collection

The Great War

WWI saw a steep rise in the cost of living and a shortage of housing. In contrast, the iron and steel industry flourished due to increased demand. At Lithgow, a shortage of skilled labour forced Charles Hoskins to hire migrant labourers and conflict soon erupted.

The war left the nation in debt and with an underclass of poor and unskilled labour. The economy slumped and thousands of workers became unemployed. Lithgow was dealt a double blow as unemployment and the influenza epidemic of 1919 hit hard.

Abandoning Lithgow

The dream of an inland industrial centre faded when Charles Hoskins made the fateful decision to abandon Lithgow in favour of Port Kembla. The blast furnace ceased operation in 1928 and The Great Depression descended on NSW and Lithgow early in 1930. The steel works finally closed in 1932.

18 October 1930, dismantling work at the blast furnaces. A E Clarke photo, Lithgow Library Learning Centre